While CPS1 is designed for all common cylinder formats, the primary impetus to develop it was the absence of a system to audition and transfer wax cylinder recordings optimally with minimal wear. The earliest of these are made of brown wax, and they are of particular interest because of their rarity, fragility, and often murky provenance.

When affordable phonographs started to find their way into homes (mid/late 1890’s), the demand for cylinders took off. But record molding wasn’t commercially viable. Records were produced in batches. So, the technical threshold to go into the business was low, and many new companies sprang up.

Little is known about these early “labels,” most of which went under in a matter of years. Typically, all we have is corporate/legal information, some advertisements, and perhaps a few short entries in The Phonoscope, the fledgling industry’s trade paper. Actual discoveries of recordings have been few and far between. But, over a century later, they still occur…

Little is known about these early “labels,” most of which went under in a matter of years. Typically, all we have is corporate/legal information, some advertisements, and perhaps a few short entries in The Phonoscope, the fledgling industry’s trade paper. Actual discoveries of recordings have been few and far between. But, over a century later, they still occur…

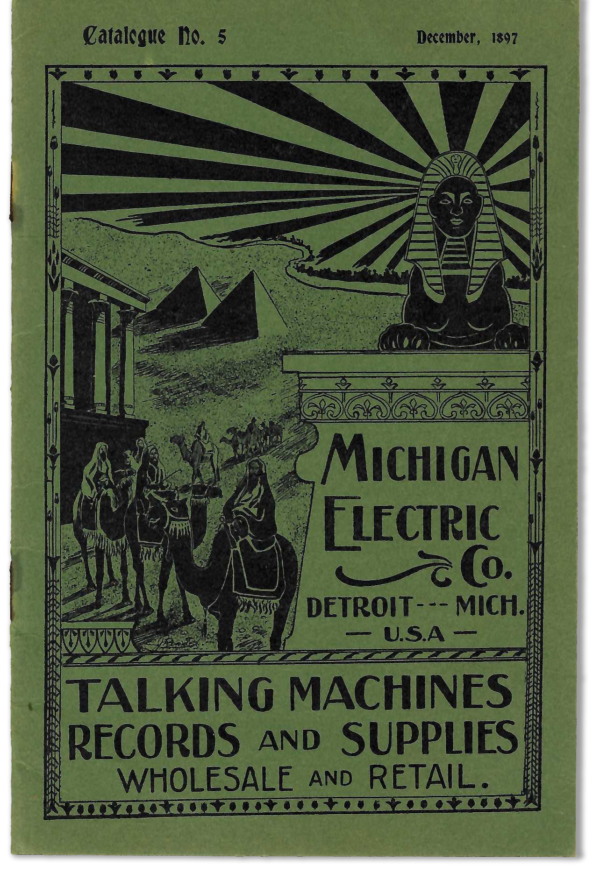

20 years ago, Michigan Electric Company was virtually unknown among early record collectors. But in about 2010, a few Michigan Electric cylinders surfaced. The records stood out: the cylinders have a blind emboss on the rim and their boxes are branded with a large rubber stamp. A few years later, a Michigan Electric catalog from 1897 was found that included a list of releases. Then, last year, a Michigan collector made an “attic find” of about 40 Michigan Electric releases still in their original dilapidated cabinet.

Working with Ken Flaherty, a CPS1 owner based outside of Detroit, we pieced together the story of Michigan Electric. It appears in the current issue of The Antique Phonograph, the quarterly publication of the Antique Phonograph Society.

Following are transfers of a few Michigan Electric cylinders, premiering (again) 122 years after they were released!

A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight, J.W. Myers

One of the most durable songs from the 1890s, is sung by one of the era’s most prolific baritones. Myers recorded for many companies, including at least two he helped manage. The bulk of his recordings, however, were made for Columbia. Significantly, perhaps, this popular title wasn’t one of them. That distinction was reserved for Len Spencer, Columbia’s leading baritone in 1898, when this cylinder was likely recorded.

That’s How the Ragtime Dance is Done, George F. Williams

Williams was a local singer and his Michigan Electric cylinders are his only found performances. The song is an early, obscure composition by Harry von Tilzer, one of the most successful and prolific composers and songwriters of the Tin Pan Alley era. Coincidentally, von Tilzer was born in Detroit in 1872 (né Aaron Gumbinsky).

The refrain is:

First you do the rag, then you Bombershay

Do the side-step, dip, then you go the other way,

Shoot along the line with a Pas-Ma-La,

Back, back, back don’t you go too far!

The Bombershay (also called the Fanny Bump) and the Pas-Ma-La are types of ragtime dances.

The primitive nature of Michigan Electric’s studio is revealed by the uneven speed of the recording machine, most noticeable at :35.

Chimes of Trinity

This sentimental ballad about New York City’s teeming populace and one of its beloved landmarks is beautifully sung by Edward M. Favor, a popular stage and recording star from the 1890s. Favor never performed the song for another label. Perhaps this version of it was made while a touring show took him to Detroit.